JAMES JOYCE’S FINNEGANS WAKE

Episode 020:

SPECIAL: INTERVIEW WITH KENJI HAYAKAWA

ON TRANSLATING THE WAKE INTO JAPANESE

2025-12-22

PODCAST AUDIO

PODCAST TRANSCRIPT

[Music: Instrumental of “The Ballad of Persse O’Reilly” with Adam Seelig on piano and Brandon Bak on drums, from the film series of Finnegans Wake. Music fades out]

Kenji Hayakawa (right) and Adam Seelig at Dublin Castle, August 2024.

Adam Seelig: Welcome to James Joyce’s divine and delirious comedy, Finnegans Wake. This episode, number 20, is a special one because joining us from his home in Ireland’s capital will be translator Kenji Hayakawa, who is currently translating Finnegans Wake into Japanese. Kenji will share his insights into Joyce’s last novel, and we’ll hear him read excerpts from his translation alongside actor Richard Harte’s readings in the original English.

Hi, I’m Adam Seelig, and I’m the director of the Finnegans Wake film series produced by One Little Goat Theatre Company.

Some good news to share: the complete film of Finnegans Wake Chapter 3 is now on our website and YouTube channel. Definitely give it a look and listen!

And as I record this near the end of 2025, I’d like to ask you all, dear listeners, to support the work of One Little Goat Theatre Company. We are a nonprofit, artist-driven, registered charity in the United States and Canada that depends on donations from individuals to make our productions, including this one, possible. So if you’re able, please take a moment to make a tax-deductible donation through our website, www.OneLittleGoat.org. Thank you on behalf of everyone involved with our productions.

[Music: Adam Seelig plays piano]

Adam Seelig: Finnegans Wake is a production of One Little Goat Theatre Company. For the next five years, One Little Goat will film and record all 17 chapters (roughly 30 Hours) of Joyce’s Finnegans Wake before live audiences in various locations, screening and releasing them along the way, with the aim of completing the entire book in time for its 90th birthday, May 4, 2029. One Little Goat Theatre Company is an official charity in Canada and the United States — if you’d like to support our work, please visit us online at www.OneLittleGoat.org to make a charitable donation. To get in touch, you’ll find our email address on the One Little Goat Theatre Company website and we’d love to hear from you.

[Music fades out]

Adam Seelig: I first heard about Kenji Hayakawa when Darina Gallagher at the James Joyce Centre in Dublin told me about him and his new Japanese translation of Finnegans Wake. So when actor Richard Harte and I were in County Dublin, Rush to film Chapter 6 of the Wake—this was in the summer of 2024—I thought I’d invite Kenji to be part of the audience. To my delight, he and his partner, Lisa, accepted. They schlepped out from their home in Dublin to our shoot in Rush, and two days later, I made the corresponding journey from Rush to Dublin to meet up with Kenji. We spent an afternoon together with Kenji taking me to one marvellous bookstore after another, and the two of us have been in touch ever since.

Before I share Kenji’s bio with you, I’ll simply say this about him: he’s brilliant, and he’s great fun. And I’ll add, his knowledge and understanding of Finnegans Wake is awesome. I feel lucky to know him and I’m thrilled he’s joining us for this special podcast episode.

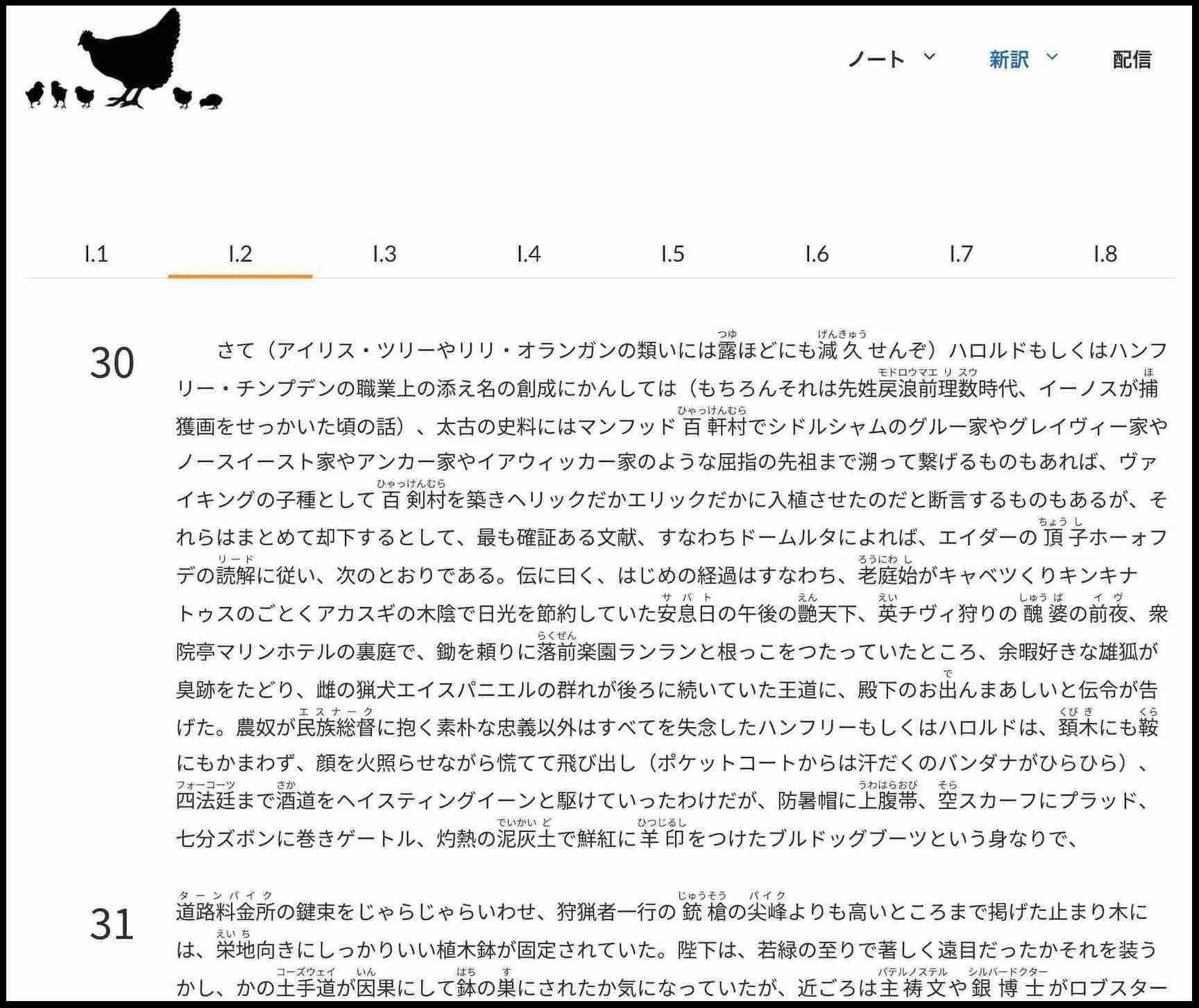

Kenji Hayakawa’s Japanese translation of Finnegans Wake Chapter 2 on finneganswake.net, edited by Yuta Imazeki.

Kenji Hayakawa is a translator and interpreter based in Dublin. Born to a Japanese mother and Irish father in Saitama, Japan, just north of Tokyo, he grew up in a bilingual family environment. After graduating from high school in Japan, Kenji attended the University of British Columbia in Vancouver for his undergraduate studies, and it was there that he started reading Finnegans Wake for the first time in a reading group run by Kevin Spenst. Following his graduation from UBC, Kenji returned to Japan, where he worked for several years before relocating to Ireland’s capital to pursue a master’s degree at University College Dublin, James Joyce’s alma mater. While working in an office job in Dublin, Kenji volunteered for several years at Sweny’s Pharmacy, a central meeting place for Joyce devotees. He is currently running a weekly livestreaming program in Japanese called “Reading Finnegans Wake” and working on his new Japanese translation of the Wake, which we’ll discuss in a moment. In June of 2025, Kenji, together with Irish literature scholar Yuta Imazeki, co-founded the Japanese website “Finnegans Web,” which is where Japanese readers can now find Kenji’s new translation of Finnegans Wake Chapter 2, published in October of 2025. And you can find a link to “Finnegans Web” on One Little Goat’s podcast web page.

Welcome, Kenji! Thank you for joining this podcast as our very first guest.

Kenji Hayakawa: I'm delighted to be with your podcast, Adam. I admire the work you are doing with Richard and I feel honored that I can talk about Finnegans Wake today with you.

AS: Thank you, Kenji. You're very kind. Let's talk about your new translation of Finnegans Wake. I'd like to start with a little bit of background. This is not the first Japanese translation of Joyce's last novel. Could you please provide us with some background on the other translations that exist?

KH: Sure. So as you rightly pointed out this is not the first Japanese translation. In fact Japanese translations have been coming out even before the publication of the full book of Finnegans Wake. So as early as 1933 the ALP fragments were being translated into Japanese by a team of translators.

AS: Incredible because Finnegans Wake was not fully published until 1939.

KH: Yes, I should have mentioned that. So, in any case, in 1933, the first ALP fragment was translated into Japanese and over the decades a few translators have been translating fragments. However, the full book was translated for the first time by Naoki Yanase and published in 1993. incidentally this is the third language to have a full length translation of Finnegans Wake at this time. So one could argue that Japanese was quite ahead of the curve vis-à-vis all languages in the world.

AS: So let's talk about your new translation and if there are already translations that exist and there's one translation of the entire text I think it's a fair question: why?

KH: Just to also add that another translation of the book albeit in an abridged form came out in 2004 translated by Kyoko Miyata who is actually a Joyce scholar and then in 2014 a revised full length translation of the whole book was published by a small independent publisher called ALP Press and this translation was done by Tatsuo Hamada who is an independent translator a retired biologist based in Japan. So quite a few translations out: two full length translations, at least one high quality abridged translation by a Joyce scholar and then some fragments before that. So to to your question of why do a new translation… Well, the biggest reason is that compared to how translators were working in the '90s and the 2000s or even before that, we have so much more resources as translators to consult, and also standards that translators are held up to are, I would argue, generally higher than a few decades ago, at least in Japan. So in this environment it's actually more surprising if a translation done and published in the 80s, 90s and 2000s still counted as adequate. In fact if even one or two major challenges were adequately addressed by these translations then I would consider that a major achievement. Listeners should remember that, for example, Google search and Wikipedia were not in existence until the year 2001. In Japan there is a major database called Japan Knowledge. this was not in service until 2001 I believe as well. And then Fweet, the perhaps most famous resource for Finnegans Wake readers was not online until 2005.

AS: So you’re drawing on a range of resources unavailable to previous translators. Kenji, I’m really interested in hearing you speak about this dialect-oriented Japanese translation that you're doing. In other words, the previous translations — and again, this is my basic understanding and you can speak to it more elaborately — is that the earlier translations were writing or translating in a kind of nationalized Japanese language, whereas what you're doing is going back into dialects. You're almost translating this into a broader, more diverse version of Japanese rather than a standardized one. Are you able to to talk about that?

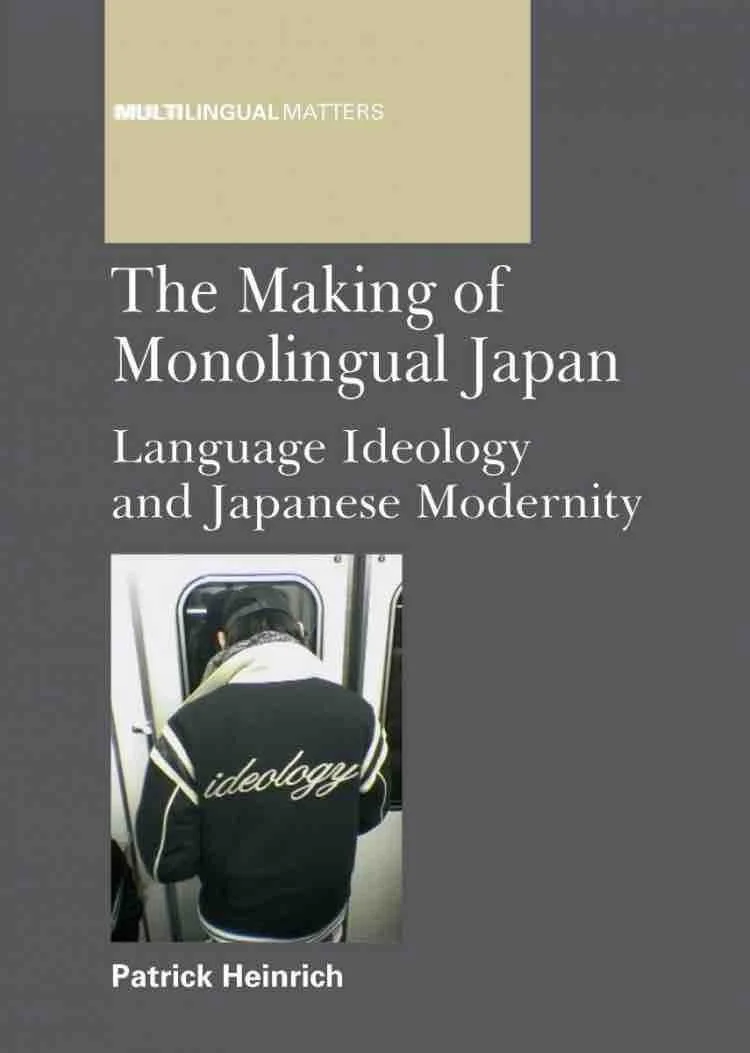

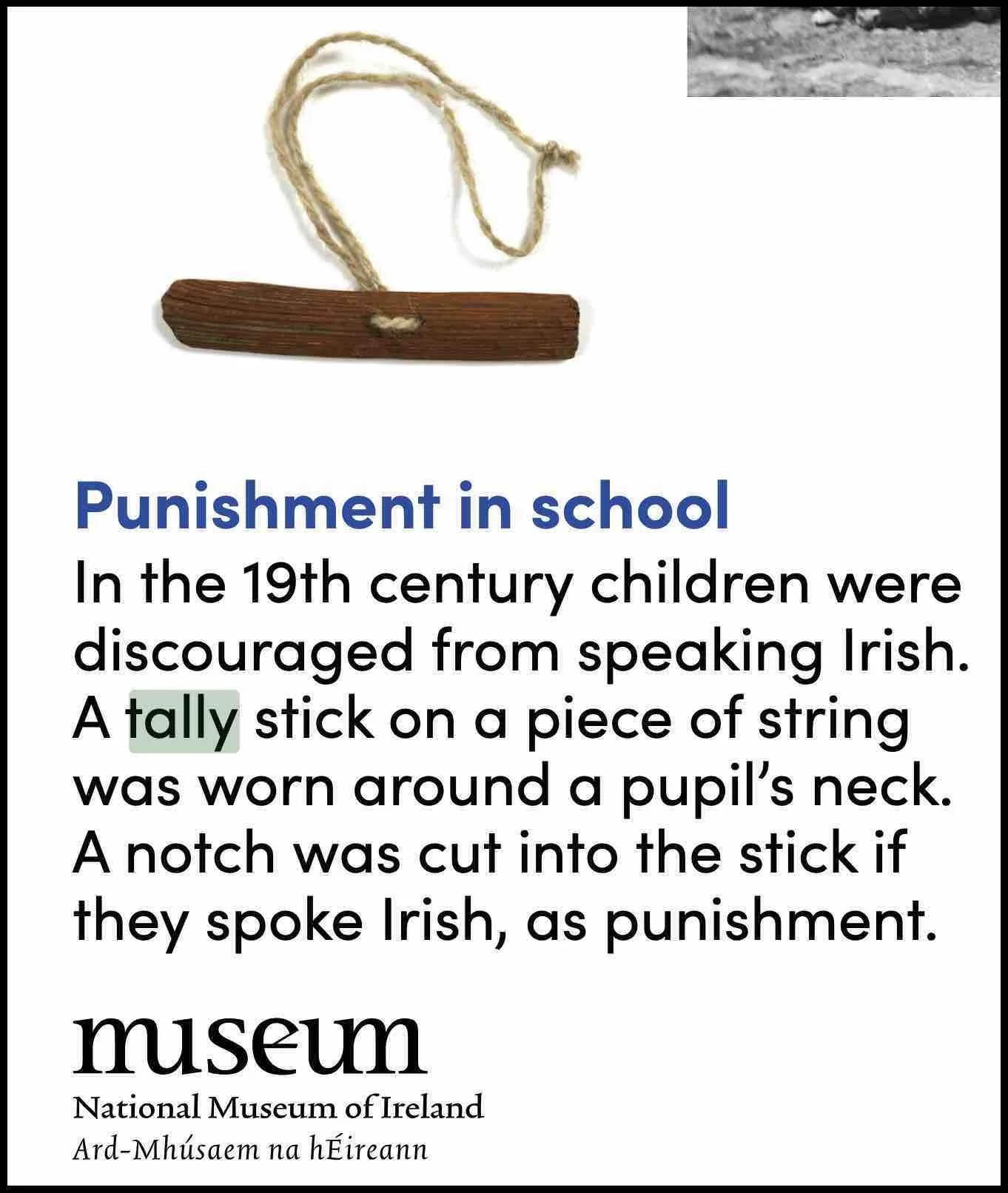

KH: Sure. So this is as you point out rightly the biggest innovation of my translation and perhaps the most important one as well in the sense that this is the element of Finnegans Wake in the original text that was least adequately captured by previous translations in my view. To give the listeners a little bit of background… Japanese as a language was standardized in the late 19th century to up to around 1900 by the newly formed modern Japanese government. And then the second phase of Japanese language history after 1900 is the introduction of the national language subject into compulsory education. Up until that point, Japanese was a hodgepodge of diverse dialects. Some scholars argue that there were hundreds of different dialects, and even today, they're categorized into at least 18 different categories of dialect. So very diverse and chaotic hodgepodge of different dialects. And then after 1900 with the introduction of national language into compulsory education, basically everyone living on the Japanese archipelago were encouraged to use standard Japanese. There's a wonderful book by Patrick Heinrich called The Making of Monolingual Japan — those who are interested in this history, I strongly recommend this resource. But any case, against that backdrop, we can understand that just as dialects were in a way marginalized and suppressed in Japan with the introduction of standard Japanese, so was Irish in Ireland during the early 19th century when compulsory education and compulsory standard English was also introduced into Irish society. Famously, Daniel O’Connell was criticized by the Irish speaking people for being perceived as promoting English over Irish, although some might argue that O’Connell was being pragmatic. But in any case, there was a parallel suppression of Irish in Ireland with the infamous tally stick system where children were made to wear these sticks and every time they spoke Irish when they're supposed to speak English, their stick will be marked with a cut and they'll be punished according to how many cuts were on this stick (bata scóir). So we have these parallels and I just wanted to as it were take advantage of this historical contingency and really pack the translation with non-standard dialect terms to the same density that Joyce packs the original text with non-standard English dialect terms as well as Irish and other foreign languages and also minority languages in Europe.

AS: So what I'm understanding about your translation is that rather than this monolingual approach, you're taking a polylingual approach and it really does match Joyce's approach. He did not write Finnegans Wake in English. He wrote it, as I've been saying for a while now on this podcast, in a dream language, which I would call rather than writing in English, writing it in languages or writing in a language. And in the same way, you're not translating into Japanese. You're translated translating into ‘Japaneses’ plural. And that is amazing. And yet, it's not possible that you, Kenji Hayakawa, speak 18 dialects. How do you then incorporate these dialects if you don't speak them all? And by the way, I should also say Joyce did not speak all 64 languages, living and dead, that are incorporated into Finnegans Wake. So, it's maybe not the fairest of question. Nevertheless, I'm curious about your relationship with these dialects.

KH: Right. That's a very good question. And as you rightly point out, Joyce wasn't fluent himself in that many languages, to be honest. Even sometimes the languages that people assume he's fluent in such as German — he wasn't that fluent and yet he packed all these different words in. And the way he did it was essentially consult dictionaries or witness contingently people using a certain phrase in a text or in conversation and he would note these phrases in his notebook and put them in the original text. So in the same spirit I didn't necessarily feel the need to study all the dialects out there and become fluent before using them. But on the other hand, I did think about okay, is it in some way disrespectful towards the dialect speakers to use their language when I am not fluent in them? And I think the answer is no. And the reason is that most of us are helpless vis-à-vis most languages anyway, right? And yet we have to somehow find a way to get along with others who don't speak our own language and speak a language that we are not competent in. So this is a very interesting negotiation as a translator to try and incorporate languages that I don't understand in a respectful way but also not discouraging myself from doing that. I guess one guiding principle was sound. So when Joyce puns across multiple languages in a word, I would often try to pun between a standard Japanese term and then a few dialect terms and then on top of that the phonetic texture of the resulting neologism. And insofar as the dialect term allowed me to construct phonetically interesting terms, then I would tend to prioritize using that particular dialect over the other dialect terms.

AS: And these dialects you're drawing from a database as I understand. Can you just give us a sense of that database where it comes from, how you access it?

KH: So the database is called Japan Knowledge, which I already mentioned, but basically it's a vast database of different dictionaries in Japan which includes the Japan dialect dictionary and essentially I can enter a term and then look for entries that contain that term. So for example, I could say ‘light’ and all the entries that contains the word ‘light’ would come up and this would include a list of dialect terms for ‘light’ and then I would look for the exact term in that list that would serve my purpose. So, as you can see, this is a very handy tool, not available to any of the previous translators. And quite frankly, without this kind of tool, I don't think it's practical for any translator to draw on this rich resource of different dialects.

AS: Wonderful. Well, speaking of light, let's get to some lightning and thunder. Let's first hear Richard Harte reading the third thunderword in Finnegans Wake. It’s one of the ten extraordinary, 100-letter words in the novel. This one occurs in Chapter 2 before “The Ballad of Persse O’Reilly” when a crowd has gathered to hear the salacious balladeer, Hosty, deliver his scandalous takedown of the protagonist HCE. And in this thunderword there’s this amazing kind of clapping from the audience that combines with crapping in light of the shit-storm, if you will, that’s about to go down. Here’s Richard Harte delivering this thunderword right before Hosty’s Ballad in Chapter 2 of Finnegans Wake.

Richard Harte: Have you here? (Some ha) Have we where? (Some

hant) Have you hered? (Others do) Have we whered (Others dont)

It’s cumming, it’s brumming! The clip, the clop! (All cla) Glass

crash. The (klikkaklakkaklaskaklopatzklatschabattacreppycrotty-

graddaghsemmihsammihnouithappluddyappladdypkonpkot!). [Applause]

AS: So that was Richard Harte reading the third thunderword from Chapter 2 of Finnegans Wake. And yeah, curious ears are wondering how does that sound in Kenji Hayakawa's new Japanese translation.

KH: All right, let's see if I can do this justice.

AS: Bravo. Very nicely done. And you kept the “kot” at the end, which is a kind of German shit. What other shits did you put into this clapping crapping word, this thunderword that's comprised of phonemes that live somewhere between clapping and crapping? Just take us through some of them. Are these across Japanese dialects that all in some way mean clapping or crapping?

KH: Okay, very interesting question. So actually I made an exception with the thunderwords to my method. Specifically for the thunderwords, I went with a purely phonetic transcription while also manipulating the spelling a little bit so that we get 100 characters in the Japanese as well. So as you have just heard it the thunderword starts with “kurika” which is pretty much exactly the same as the original which is “klikka” and then it ends as you said exactly the same as Richard. And the reason why I took an exception with the thunderwords and went with the purely phonetic transcription is because I see the thunderword as transcending any kind of national language. To me, the thunderword is closer to a magic incantation rather than something that has to be semantically translated into Japanese. The other idea I had with the translation here was actually inspired by a Joyce quote, again I'm terrible at remembering these things exactly, but if I remember correctly, then Joyce said something to the effect that he hoped that if someone in, let's say, [_____] picked up his book and found a local river name in Finnegans Wake and smiled at the fact, then he would have been glad to have written the book. So in a similar spirit to me, if someone masters the thunderword in this Japanese translation and is able to read it out loud to let's say an Irish audience in an Irish pub setting and the Irish audience, even though they don't have a word of Japanese, recognize this thunderword, then this is an example of the work transcending national linguistic borders and actually connecting people. Conversely, as a translator, I want the Japanese readers to be curious about other languages. So, by reading this thunderword, which is essentially nonsense in Japanese, most readers will immediately notice that it has some kind of meaning in the original, but not in this Japanese version. So, well, what does it mean in the original? And they will learn a variety of different ways of saying excrements and clapping and so on. And again this experience of reaching over to another language, another writing system and learning about that language on its own terms is an experience that I do want to encourage through this translation. So those were some of the motivations behind this choice.

AS: I think it's lovely that you have this transcendent approach. At the same time you're moving across Japanese dialects. You're working polyvocally, polylingually within one language and then you're also working beyond the borders which is appropriate for a natural phenomenon like thunder and lightning which of course is truly universal. So that's a brilliant and inspired choice for sure.

Well, I'd love to turn to another excerpt and hear some more from your translation. It's wonderful to hear Richard right before your translation. I can really start to hear some of these rhythmic semblances and affinities. So, let's take it away here. We'll hear another excerpt from from Richard. This is also from Chapter 2, which you have translated Kenji. We'll talk about that in one moment: why you started with Chapter 2 rather than starting with Chapter 1 of Finnegans Wake. First, let's give a listen to page 39, lines 2 to13, roughly the top of page 39. What's happened here in Chapter 2 is we've been introduced to HCE and the rumour mill is spreading wildly already at this point. He had an encounter with a Cad, the Cad went home and told his spouse, and there's a kind of rumour about HCE, salacious rumours. Again, I keep coming back to that word because there is really a lot of sin that's associated with HCE. These are alleged sins. Did they actually happen? We're not quite sure. But what we do know is that Joyce is really interested in the movement of language, and language does not move any faster than when people are gossiping. So we have this rumour mill and gossip, a grapevine, etc. It's moving from the Cad to the spouse and the spouse to a priest and then… it goes on to a number of people. We then get to Philly Thurnston I think is heading to the racetracks if I got that right. And now we're at the top of 39. And now the rumour is spreading so quickly it takes on a quality of horse racing. That's the speed at which it's moving. So, we're at the horse races now. We're going to hear Richard read the top of page 39 from chapter 2 of Finnegans Wake and then we'll hear Kenji. Okay, take it away, Richard.

Richard Harte: … during a priestly flutter for safe and sane bets at the

hippic runfields of breezy Baldoyle on a date (W. W. goes

through the cald) easily capable of rememberance by all pickers-

up of events national and Dublin details, the doubles of Perkin

and Paullock, peer and prole, when the classic Encourage Hackney

Plate was captured by two noses in a stablecloth finish, ek and nek,

some and none, evelo nevelo, from the cream colt Bold Boy

Cromwell after a clever getaway by Captain Chaplain Blount’s

roe hinny Saint Dalough, Drummer Coxon, nondepict third, at

breakneck odds, thanks to you great little, bonny little, portey

little, Winny Widger! you’re all their nappies! who in his never-

rip mud and purpular cap was surely leagues unlike any other

phantomweight that ever toppitt our timber maggies. [Applause]

AS: So that was Richard Harte reading the horse race, if you will, page 39 of Finnegans Wake. Would love to hear your version of it. And maybe well, why don't we just get into it and then we'll talk about how how you actually rendered this. So, Kenji Hayakawa, this is your new translation from the Japanese, page 39 of Finnegans Wake.

KH: All right, here we go.

AS: Fantastic. Fantastic. That is great. Kenji, how did you… did you go to the races? Did you did you lose a lot of money in order to translate this passage? How did you get that sound?

KH: Unfortunately, well, fortunately or unfortunately, because I'm based in Dublin, I couldn't, you know, literally fly to Japan and go to a Japanese horse race. But I did feel that listening to horse race commentary in Japanese will greatly help me in rendering this in the right rhythm. So, I listened to about I think one hour of non-stop horse racing commentary in Japanese over and over again. So, in reality, I probably spent a few hours listening to it. But what I noticed was that in horse race commentary, it's almost like, as you said in the introduction to this clip, that the words and the intonation follow the rhythm of the race itself. So when the race heats up, the commentators also become more lively and articulate. when the race is slow or when there's an obvious outcome, let's say, then the commentators are less lively, maybe a little bit more calm, composed, reflective. So, in this example, it's very clear that Winny Widger is somewhat of a surprising winner. At least the characters who are depicted in this chapter seem to have failed to predict Winny Widger taking the cup. So the commentators are clearly quite taken aback by this. Nonetheless, they're very excited. So I just wanted to capture that excitement not only in terms of semantics but also in terms of the intonation in Japanese.

AS: Love that section and I love it in in both languages. And I want to just ask you that question as promised. Chapter 2, why did you start with chapter 2 and not in the obvious place which would be to begin translating Finnegans Wake into Japanese with Chapter 1?

KH: Very good question and the short answer is that I felt that Chapter 1 misleads readers into thinking that this chapter is paradigmatic of how the rest of the book is written. So what I mean is Chapter 1 is very special and it has a distinct style, very complicated structure. An earlier version was written quite early on, I think 1926 1927 if I remember correctly, and originally when Joyce was writing Book One he planned to begin with Chapter 2 not 1. And then he wanted the book to have six chapters not eight and the two chapters that were not in the book originally were Chapter 1 and Chapter 6 (‘the quiz’).

AS: So in a sense, you're following his natural instinct, which was to start at what is now Chapter 2. That was going to be his beginning, but instead he added this Chapter 1. And again, for shorthand, I'm calling it an overture that sounds many of the themes that we will hear later in the novel. Is that then a fair answer to the question, that that's why you started with Chapter 2: that it’s kind of a way in for both you as a translator and for your readers?

KH: Yes, that's correct. And also if the readers start with Chapter 2, then they will as it were, in my view anyway, more accurately understand the rest of the book as following an actually quite intelligible narrative structure. So that might be a surprising claim for those who start with Chapter 1. However, Chapters 2, 3 and 4 comprise what's commonly called the Humphriad, and they do have a very clear narrative structure. And then chapters 5, 7 and 8 also each have a very clear theme: ALP's letter for Chapter 5, Shem's as it were self flagellating autobiography as narrated by Shaun in Chapter 7, and then finally the two washerwomen gossiping about ALP in Chapter 8.

AS: So if we pulled Chapters 1 and 6 out of Book One of Finnegans Wake — and anyone who wants maybe to cut back on some reading and get through this a little faster, just take out Chapters 1 and 6. No big deal. You're going to be fine.

Kenji, can you give us a window onto your translation process: what goes into translating let’s say a page of Finnegans Wake?

KH: So, it's not my sole effort. Yuta Imazeki, the Tokyo based Irish literature scholar, is a close collaborator of mine, and he checks not only the translation, but also the notes that are made in preparation to the translation. And then we also have PhD candidate, soon to hopefully be doctor of Chinese philosophy in Tokyo University, Kohei Ise, who is taking a look at the Chinese words in the translation, since we decided to render all the Latin terms in Chinese. And basically the starting point for me for translating this book is the weekly livestream program that I've been running now for over three years where essentially every Friday we gather online and read a page or two of Finnegans Wake for about 2 hours and again I draw on all the online resources to decode the text and participants can write and share their interpretation in chat. We generally have a very productive and fun conversation every week. But that's step one. And then step two would be preparing the notes with Yuta on a more detailed series of notes describing what's referenced in the text. And here we go a few steps beyond the usual resources such as [Roland] McHugh and [Adaline] Glasheen and so on. But we also draw on material directly available on archive.org (wonderful website by the way). And we use Wictionary a lot as well. We vet every claim made on Fweet or McHugh and wiki or whichever other resource we're using. And then we add our own insights and references that we've discovered as well. So we have arguably one of the most thorough annotations to the original text ready by that point and that is also shared on our website Finnegans Web in Japanese.

AS: And we'll link to that in our podcast post on One Little Goat.

KH: So at that point we're spending minimum 10 hours maybe 15 hours per page purely for the purpose of annotation and then we're ready to start our first draft. So at that point I start writing my first draft translation. And at that point in addition to all the notes we used I also make heavy use of the James Joyce Digital Archive page. That's a fantastic resource. Essentially, this website allows you to reference every past draft on record of a chapter or a section.

AS: And I'll add to our our listeners if if you don't mind my jumping in for one sec that also on that same site, the James Joyce Digital Archive, is a wonderful Chicken Guide. The Chicken Guide is a kind of lay language version, simple summary of what what's happened in each chapter. Marvelous guide. Carry on. Sorry.

KH: Yeah, absolutely. And again, this resource was not available to any of the previous translators. So, I'm really privileged to be able to use all of these resources. The first draft maybe takes about 15 hours to complete per page. And then that is checked by Yuta again, revised by me, and that's how it's done. So, it's maybe minimum 30 hours per page spent all starting with the

AS: Minimum!

KH: Yeah. And in this process, I gradually came to realize that starting with Chapter 2 was more rational than what I initially thought. Initially I just thought, well, it's easier to start with Chapter 2 than Chapter 1. So I will start with Chapter 2, make all my mistakes, and when I feel I'm ready to take on Chapter 1, I might go back to it. But the more I go through this iteration, the more I'm realizing that for multiple reasons, Chapter 1 should probably be reserved for a much later time to be worked on compared to the other chapters.

AS: What I like about your process and your description here is that while you are clearly the translator of this new translation, it’s also on a certain level a group effort.

KH: Yeah, I'm glad that you really emphasized the community element because the reason why I'm working on this text now is because of a reading group to begin with. So the first time I heard of Finnegans Wake was 15 years ago now — goodness — in Vancouver when I was still doing my undergrad at UBC Vancouver. And I was one day listening to NPR on my bike and the program was interviewing Kevin Spenst, a local poet. And Kevin said that he's running this monthly reading group of a book called Finnegans Wake and they're spending a month to read three pages tops, maybe even two. I was thinking, well, that is quite extraordinary for two reasons. One: NPR interviews reading group organizers. That's awesome. And then secondly, this reading group is going to spend according to them anyway 17 years reading one book. How does that work? So I picked up a copy of Finnegans Wake in the library when I got to campus and understood that yes indeed it probably takes 17 years to read this thing. And, for some reason I bought and brought the Japanese translation of Finnegans Wake to Vancouver at the time. I think I just bought it because it was a famous translation and I wanted a copy, but I had no idea, I mean, I hadn't opened it and I had no idea what was written in it. So, I go to this reading group and everyone's so nice. Amy Logan, Kim Koeg and Mark Logan and others. And basically they welcomed me with open arms and there was a multilingual exchange, right? So someone would understand German, others would know a bit of Greek. I believe Kevin had the French translation of Finnegans Wake at the reading. So we had a bit of French input there. And then I had my Japanese translation. We weren't scholars, so we weren't debating whether anyone's interpretation was plausible or whether one was better than the other, but we were more just sort of sharing what we saw in the text. And this was a surprisingly satisfying experience. So yeah, that experience stuck with me and every other reading group I've been a part of or organized essentially is in the spirit of that reading group in Vancouver of Kevin and Amy and so forth. Few books kind of not only make an impact on you personally but also make an impact on community in that way. And again by putting this translation on the internet, I hope for many people across the country in Japan to access this text and hopefully start their own reading groups and see if something comes out of that. Yes. So that's that's kind of where it's at.

AS: Fantastic. Well, why don't we take it to another excerpt from Richard followed by Kenji's translation of Finnegans Wake. And I'm thinking that it would be fun for us to hear “The Ballad of Persse O’Reilly.” Why don't we play the first stanza, the first verse from Richard's recording and then we can hear that first verse in Kenji's new translation,

Richard Harte: "THE BALLAD OF PERSSE O’REILLY." [Music]

Have you heard of one Humpty Dumpty

How he fell with a roll and a rumble

And curled up like Lord Olofa Crumple

By the butt of the Magazine Wall,

(Chorus) Of the Magazine Wall,

Hump, helmet and all?

AS: And so there we have Richard singing, performing the first verse of “The Ballad of Persse O’Reilly,” which opens with the fall of that famous Mother Goose character, Humpty Dumpty. And take it away, Kenji Hayakawa. This is your new Japanese translation of that first verse.

KH: Okay. Is singing encouraged in this case?

AS: Of course it is.

KH: Oh my goodness.

AS: You got this, Kenji.

KH: So, a little bit of context is when Adam was in Tokyo and we did the event, I recorded this part and it was probably one of the most surreal experiences of my life where I was just singing at the top of my voice in my kitchen. I hope my neighbours will not know completely put me on their blacklist for this, but, in any case, okay, let's go.

「パース・オライリーのバラッド」

AS: Very nice. Very nice. And I'm sure your neighbours will forgive you if you've startled them in any way. You just tell them it's in the name of Irish literature and they'll understand.

KH: I will say this, it's not quite the same without this excellent piano accompaniment.

AS: We have an unfair advantage by having piano accompaniment. It's true in our version.

While we’re on The Ballad of Persse O’Reilly, you recently brought to my attention a political moment that came up vis-à-vis the Ballad. Would you be okay to introduce us to some of the political dimensions around the song?

KH: I take it you're referring to the first No Kings protest in the United States that happened in May. So this protest included a man holding up a cardboard with two lines of a verse from The Ballad of Persse O’Reilly, and on the edge of the cardboard was also written “from Finnegans Wake” just in case, you know, people were not sure where it was from, wanted that reference.

AS: That's good. Always good to footnote your political signs.

KH: Yes. Exactly. Cite your sources. The two lines were:

So snug he was in his hotel premises sumptuous

But soon we’ll bonfire all his trash, tricks and trumpery

And of course, we've got the word Trump in there. In this context, Trumpery just means nonsense or gobbledegook. “So snug he was in his hotel premises sumptuous” — [US President Donald] Trump is a self-styled real estate businessman, so of course the reference to hotel is appropriate.

AS: And owns a hotel in Washington.

No Kings protest, Washington DC, 2025-10-18 (source: Politico).

KH: Yeah, as well as a golf course on the west coast of Ireland, and many other places. So although the broader kind of political implication of The Ballad is very interesting, in the context of the No King's protest it was obviously used in a straightforward way. So what I mean by that is in the original text, Hosty composed a ballad to essentially magnify and exaggerate all the negative things that people have said about HCE. And given that HCE is thought to have been born in the UK in Sidlesham that he's presumed to be British — in fact he says “British to my backbone tongue.” So you know presumably he speaks British English. So there is this HCE the quintessential British figure being arguably slandered, but perhaps a grain of truth in that as well, by all the Liffey-side people as Joyce calls them. So all the Irish people — and Hosty is a representative of this Irish Liffey-side crowd who all seem to get a kick out of slandering HCE the quintessential British figure. But Joyce is also making fun of Hosty by showing how essentially a whole nation is united to go after this one helpless pub owner in Chapelizod [Dublin]. So as a reader, we're not sure how we're supposed to feel about this ballad. I mean on the one hand, yes it's a criticism of British colonialism and imperialism and all the violence the British have done in Ireland and all the rest, but on the other hand it's also a criticism of a kind of a reactionary nationalism by the Irish people who kind of define themselves in a negative way vis-à-vis something that they all reject, namely British rule and British culture and so on. And so in the No Kings case it's taken in the straightforward way of you know oppressed people protesting against this kind of arch enemy but in the text in the original text the act of composing this song is also being made fun of. So Joyce is not saying ‘everyone should just be up in arms and compose rants to curse the leader.’

AS: So he's able to play it both ways. He's at once able to enjoy the radical spirit behind taking someone down on the one hand and at the same time lampooning or parodying that and recognizing how fatuous or how much hot air there is sometimes behind that as well.

KH: Yeah. And again, I think Richard's performance of the ballad encapsulates both aspects very well.

AS: I agree completely. Let’s turn our attention now to the famous opening line of Finnegans Wake in your new Japanese translation, Kenji. I’ll start by playing Richard’s reading first and then we’ll turn to you. Here’s Richard:

Richard Harte: riverrun, past Eve and Adam's, from swerve of shore to bend

of bay, brings us by a commodius vicus of recirculation back to

Howth Castle and Environs.

AS: That was Richard reading the opening sentence/paragraph of Finnegans Wake. Those are the first few lines. Would love to hear it now in Kenji Hayakawa's new Japanese translation.

KH:

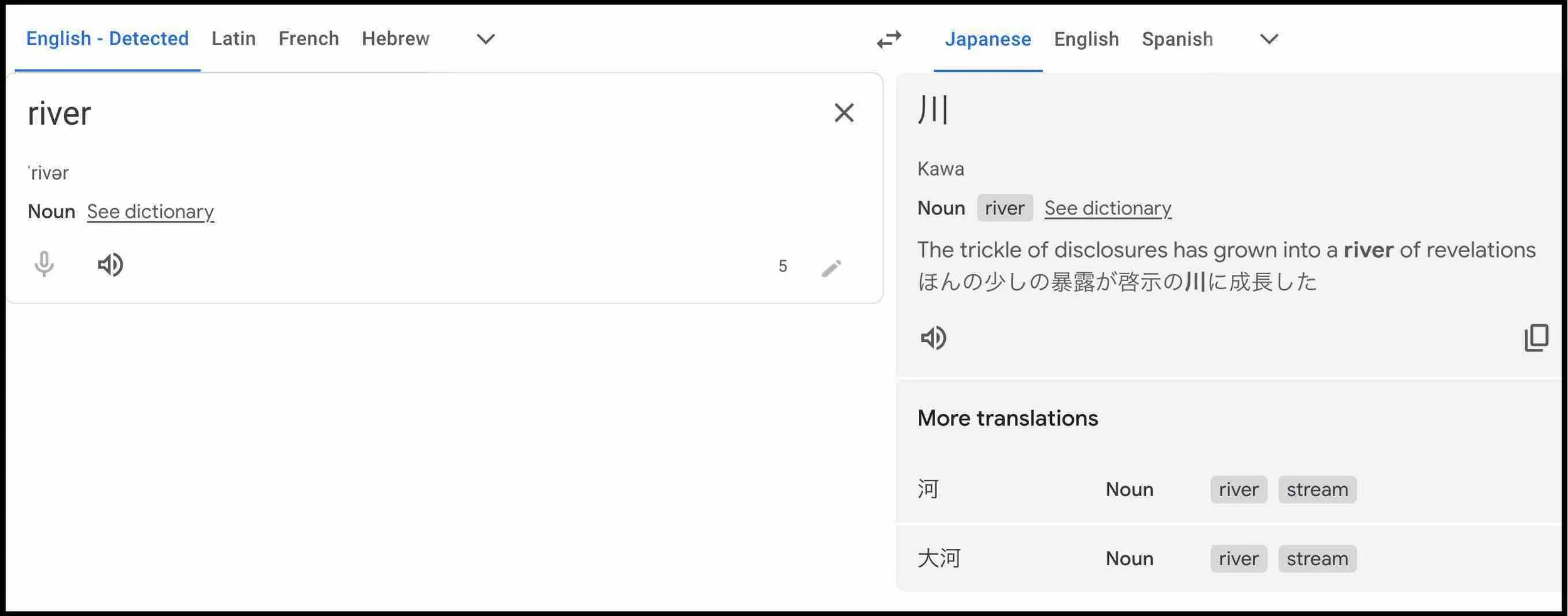

AS: Lovely. You have captured that first rhythmic stamp. “kawaran” — “riverrun.” I'm hearing something very close sonically to “riverrun.”

KH: Well, there are several things to note. So firstly, the original word “riverrun” sounds very natural in English. So we immediately know that we're talking about a river that is running. And then we have all these secondary connotations in French. We have dreaming river and in Italian return or riverrano and so on. So, I purposefully focused on the phonetic texture at perhaps the expense of some of the secondary meanings. In Japanese, river is kawa. There really isn't any other way of saying river that sounds natural. So, kawa was a bit of a lock for me, no pun intended. And then ran is another conscious choice in that it's kind of similar to the thunderword, but again I wanted this word to transcend linguistic boundaries to a certain extent. And ran is a very natural art to add to pretty much any word in Japanese. It's not commonly used in modern Japanese but for example in premodern classical Japanese you can conjugate many verbs by putting ran at the end and then in the case I guess even in modern Japanese for example in kawaran it's a conjugation of the verb kawaru which means to change but kawaran makes it not change so it's river run and then it also means doesn't change or not changing in Japanese. So that captures the Italian riverano, a return in the sense that we're telling the same story that is not changing.

I wanted also to find a way to fit the French rêver, to dream. But at the end of the day, I thought overcomplicating this word and ruining the phonetic texture of it was not worth the price of putting the word ‘dream’ in. But if anyone has a solution, then I'm all ears.

AS: You've captured river, you've captured — and tell me if I'm getting this right — a kind of sense of constancy. Would that be fair to say?

KH: Yeah. I mean, not changing, therefore constant.

AS: Yeah. So there's something eternal at play here. And gods willing, the earth willing, the rivers will run forever.

Kenji, I'm wondering about the Irish cultural context, never mind Gaelic and Irish language, which plays a a strong linguistic role throughout Finnegans Wake, but I'm talking about just Irishness. I mean, part of what has been so wonderful for me in reading the Wake is that I'm reading it with Richard Harte, who was born and raised in Dublin. So, he has this amazing Irish sense, Irish history, I mean, he brings that to his readings. And so, there's a lot of reference there that he naturally understands that I, as someone who grew up in Vancouver, British Columbia, did not really access, and I don't come from an Irish background. So what do you do then to, let's call it, culturally translate some of this material over to Japanese readers who by and large are not Irish and most of whom have not set foot in Ireland. How do you make this work let's say available to them on the cultural Irish level?

KH: Right. Thanks for this question because it's a very important one for me. And again this goes back to my approach of using non-standard Japanese at the same density as the original text because again Irish English is very inflected and kind of a language unto itself sometimes, very distinct from standard American English and even from standard British English. So, it didn't really make sense for me to pretend as if standard Japanese would be adequate. What I really took care to do was to preserve all the Irish references, and I made sure as many proper names are included faithfully as possible. So right off the bat, for example, the original text [of Chapter 2] is:

Now (to forebare for ever solittle of Iris Trees and Lili O’Rangans)

And straight away we have a reference to British actress Iris Tree as well as possibly a reference to lily brunello or the orange lily. And these references are preserved as

さて(アイリス・ツリーやリリ・オランガンの類いには露ほどにも減久せんぞ)

So right off the bat, reserve the name. And then Humphrey Chimpden is Hanfuree Chinpuden [ハンフリー・チンプデン]; the Iawikkah [イアウィッカー].

AS: I almost feel like I could be translating this into Japanese at this point.

KH: Exactly. So some might feel, especially translators who are good at creative approaches, might feel that this is a little too straightforward. But for me that's the whole point; that you hear a name like Iris Tree or Earwicker and you can see that I could have translated it in some creative way to make it sound more Japanese but I deliberately kept it as it is.

AS: So you’re in an interesting position. You are translating into Japanese, which is historically related to Chinese, but you don’t have other countries you can go to with Japanese script. When someone is translating Finnegans Wake into German they can draw on so many other languages out there that are using the Latin alphabet, from English to French to a language like modern Turkish, modern Turkish is written with Latin letters. So do you feel, I’ll put it simply, disadvantaged?

KH: Yeah, that's a very interesting question and I haven't completely made up my mind on this, but I can share my thought process and again I would be very interested in hearing what you think as well as what listeners think about this. So from a Japanese perspective, we're using a script that's only used in the Japanese language. So what that means is that if I wanted to write something in Chinese, then it's in a totally different script. So I cannot naturally pun across two different languages using the same script. Korean has a different script again. So, if I want to pun with Korean words, then I can't do it naturally in the Japanese script except in some contrived way, whereas what you're implying in your question is that if you're writing in German, you're still using the Latin script shared by Spanish, Italian, Portuguese, English, French, as well as a whole host of minority languages as well. And Latin of course. So you can naturally pun across these languages without any additional contrivances. But then a challenge becomes: how do you make the Latin text, for example, how do you make the German translation distinctly German? That's the challenge for the German translator. And what I mean by that is in the Japanese script, because I'm using Japanese script, yes, on the one hand it's hard to construct multilingual puns, but on the other hand it's just very self-evidently Japanese. So I don't have to do anything except write in the script and to make it Japanese. Whereas in the German script, if you go too overboard with the multilingual puns, then it just starts to kind of lose a sense of what the base language is. I mean, the English already at times loses that sense as well. And you're almost feeling like, am I reading Albanian instead of English here? Or, you know, isn't this just basically Dutch? So it's kind of interesting what it means to translate into a language. I mean there's that very kind of you know common rather in my view a little bit trite joke of, like, well first we have to translate it into English, which is kind of correct but…

AS: And it is something that on the James Joyce Digital Archive they've done handily, they've done a beautiful job of translating, so to speak, each chapter. Again I can't recommend it highly enough — wonderful work

KH: And talking about the James Joyce Digital Archive, the thing is, when you look at the earlier drafts of each chapter it's very clear that Joyce thought about the plot in pretty much standard English, very readable, and very few multilingual puns, and a lot of the puns, dialects, local slang terms, etc. were added through up to a dozen revisions. So, it's on the one hand, it is definitely an English text, the base language was English, but the finished product makes you feel like it's not really following one base language at times. And to say that, okay, now I'm translating this into German or Italian means you somehow have to make it feel like the base language is German or Italian. And that is a distinct kind of challenge that a Japanese translator or a Chinese translator might not necessarily face.

AS: So in a certain sense you have an advantage over those Latin scripts of German, Spanish and so on who are translating Finnegans Wake, and good luck to them all.

KH: My well wishes go to these translators as much as yours, Adam.

AS: Kenji, it’s been a pleasure having you on this podcast; our very first guest, I’m honoured that you joined, and thrilled that you’re making such extraordinary headway with this new Japanese translation of FW. I learn so much about the text from conversations with you. I hope people have enjoyed likewise hearing some of your insights into your process and into the novel more broadly. Thank you so much for this time; really appreciate it.

KH: Pleasure is all mine. Thank you very much. And hopefully we get to talk about this continuously in the years to come.

AS: That was translator Kenji Hayakawa joining our podcast in December of 2025 from his home in Dublin. Many thanks again to Kenji.

For those wanting to know more about some of the topics Kenji discussed, I will link on One Little Goat Theatre Company’s podcast web page to two resources he recommends.

(1) Patrick O'Neill’s book, Finnegans Wakes: Tales of Translation, published in my backyard by University of Toronto Press.

And (2) The Making of Monolingual Japan: Language Ideology and Japanese Modernity, by Patrick Heinrich, published in England by Multilingual Matters.

I have of course also linked to finneganswake.net, where you can find Kenji’s Japanese translation of and annotations to Finnegans Wake.

Join us on new year’s day of 2026 for Episode 21 to hear actor Richard Harte continue his reading/performance of Chapter 4 of Finnegans Wake. In the meantime, I’m wishing you all peace and health for 2026.

[Music: Instrumental of “Roll, Jordan, Roll” with Adam Seelig on piano and Brandon Bak on drums, from the film of Finnegans Wake Ch03.]

Adam Seelig: For more on One Little Goat’s Finnegans Wake project, including transcripts of this podcast and the complete films of Chapters 1, 2 and 3, visit our website at OneLittleGoat.org. And to hear about upcoming performances and screenings, join our mailing list, also on our website.

One Little Goat Theatre Company is a nonprofit, artist-driven, registered charity in the United States and Canada that depends on donations from individuals to make our productions, including this one, possible. If you’re able, please make a tax-deductible donation through our website, www.OneLittleGoat.org

Finnegans Wake is made possible by Friends of One Little Goat Theatre Company and the Emigrant Support Programme of the government of Ireland. Thank you for your support!

And thank you for listening!

[Music fades out]

[End of Ep020]

Mentioned: translator Kenji Hayakawa, existing Japanese translations of Finnegans Wake, why translate FW into Japanese, Kenji’s translation and annotations (with Yuta Imazeki) on https://finneganswake.net/, Japan Knowledge database, Fweet, standardized Japanese, 18 categories of Japanese dialects, drawing on nonstandard Japanese dialect terms to translate FW, suppression of Irish language under British rule, translating into “Japaneses” plural much as Joyce wrote FW in multiple languages (dream language), translating puns and sound, thunderword #3 in English and Japanese, thunderword as a trans-lingual magical incantation, ‘horserace’ excerpt from Ch02 in English and Japanese, starting with Ch02 rather than Ch01, Vancouver FW reading group led by Kevin Spenst, community aspect of reading and translating FW, “Ballad of Persse O’Reilly” excerpt in English and Japanese, political dimensions of “Ballad,” No Kings protest against American President Donald Trump, opening line of FW in English and Japanese, “riverrun” as “Kawaran” meaning “unchanging” in Japanese, “Kaway” meaning “river” in Japanese, ‘cultural translation’ of Irish culture, Japanese script vs Latin-letter scripts (English, German, etc.), James Joyce Digital Archive.

Resources: Transcript for this episode, including the text of Finnegans Wake.

Finnegans Wakes: Tales of Translation, Patrick O'Neill. University of Toronto, 2022.

The Making of Monolingual Japan: Language Ideology and Japanese Modernity, Patrick Heinrich. Bristol, UK, Multilingual Matters, 2012.

Kenji Hayakawa’s Japanese translation of FW Ch02 online.

Note: Kenji Hayakawa will be speaking at the James Joyce Centre in Dublin on 2026-01-15.